New Scrutiny Falls on the Economic and Environmental Costs of a Billion Dollar IndustryAquifers (underground reservoirs) are being depleted by overdevelopment of the land and an increasing population. Global warming is changing weather patterns around the world, causing droughts in densely populated regions and flooding in others where overdevelopment has paved over the land's ability to replenish the aquifers. The flood waters run off instead to places where it (usually) becomes unusable by man.

America's water systems, built and paid for originally by the American taxpayer, is being sold off to multinational corporations. The water is being pumped out of aquifers, bottled and shipped out to the highest bidders.

If not in our lifetime, but certainly in our children's, San Franciscans will be facing thirst, dehydration and death because tap water, taken over by multi-national corporations, will be shipped to those who can pay top dollar for it.

PepsiCo delivery man Nick Jones unloads Aquafina water and other Pepsi products while making a delivery in Tualatin, Ore., in a file photo of April 26, 2006. The label on Aquafina water bottles will soon be changed to spell out that the drink comes from the same source as tap water, the brand's owner PepsiCo said Friday, July 27, 2007. (AP Photo/Don Ryan, file)Democracy Now! reports:

PepsiCo delivery man Nick Jones unloads Aquafina water and other Pepsi products while making a delivery in Tualatin, Ore., in a file photo of April 26, 2006. The label on Aquafina water bottles will soon be changed to spell out that the drink comes from the same source as tap water, the brand's owner PepsiCo said Friday, July 27, 2007. (AP Photo/Don Ryan, file)Democracy Now! reports:AMY GOODMAN: The soft drink giant Pepsi has been forced to make an embarrassing admission: its bestselling Aquafina bottled water is nothing more than tap water. Last week, Pepsi agreed to change the labels of Aquafina to indicate the water comes from a public water source. Pepsi agreed to change its label under pressure from the advocacy group Corporate Accountability International, which has been leading an increasingly successful campaign against bottled water.

In San Francisco, Mayor Gavin Newsom recently banned city departments from using city money to buy any kind of bottled water. In New York, local residents are being urged to drink tap water. The US Conference of Mayors has passed a resolution that highlighted the importance of municipal water and called for more scrutiny of the impact of bottled water on city waste.

The environmental impact of the country's obsession with bottled water has been staggering. Each day an estimated sixty million plastic water bottles are thrown away. Most are not recycled. The Pacific Institute has estimated twenty million barrels of oil are used each year to make the plastic for water bottles.

Economically, it makes sense to stop buying bottled water, as well. The Arizona Daily Star recently examined the cost difference between bottled water and water from the city's municipal supply. A half-liter of Pepsi's Aquafina at a Tucson convenience store costs $1.39. The bottle contains purified water from the Tucson water supply. From the tap, you can pour over 6.4 gallons for a penny. That makes the bottled stuff about 7,000 times more expensive, even though Aquafina is using the same source of water.

Gigi Kellett of Corporate Accountability International joins us in Boston, the group spearheading the Think Outside the Bottle campaign. We're also joined by freelance writer Michael Blanding. Last year he wrote an article for alternet.org called “The Bottled Water Lie.” We welcome you both to Democracy Now!

I want to begin with Gigi Kellett. Talk about Pepsi's admission.

GIGI KELLETT: Well, after a couple of years of our Think Outside the Bottle campaign, we have been asking of the bottled water corporations to come clean about where they get their water, what is the source of the water that they're bottling, because most people don't know that Pepsi's Aquafina, Coke's Dasani, comes from our public water systems. And so, after thousands of phone calls, thousands of public comments submitted to the corporation, and us taking these demands directly to the corporation’s annual shareholder meeting this year, Pepsi last week made the announcement that it would reveal that it gets its water from our public water systems.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, where exactly does Pepsi get it? Which public water supply?

GIGI KELLETT: Well, that is the issue that we're really looking at next, is what cities are they bottling the water in. You know, here in Massachusetts, it's coming from Ayre, Massachusetts. So we want to make sure that on those bottles it says: “Public water source: Ayre, Massachusetts.” That way, people know exactly what they're getting when they're buying that Aquafina bottled water.

AMY GOODMAN: Ayre being the name of a town in Massachusetts.

GIGI KELLETT: Ayre is the name of a town, right. Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: And what happens to the town? They have their public water supply, and they have the plant for Pepsi?

GIGI KELLETT: That's right. We want to make sure that -- you know, Pepsi has certainly taken a lead on this for the bottled water industry, and we want to make sure that Coke and Nestle also follow suit. One of the things that we're finding as we're talking to people about this issue on the street is that they don't know where the water is coming from. And the bottled water corporations have spent tens of millions of dollars on ads that make people think that bottled water is somehow better, cleaner, safer than our public water systems. And in reality, we know that that's not true. And so, we want to make sure that we're increasing our people's confidence in their public water systems once again and knowing that we need to be investing in our public systems.

AMY GOODMAN: Gigi, can you go further who owns what? You mention Nestle. What does Nestle own?

GIGI KELLETT: Nestle owns several dozen brands of bottled water. The bottled water brand they source from our public water systems is called Nestle Pure Life. They also own Poland Spring, Ozarka, Arrowhead. The list goes on. And regionally, it's distributed across the country. And then we also have Coca-Cola, which bottles Dasani water, and, or course, Pepsi with Aquafina.

AMY GOODMAN: And when it comes to being tap water, what is the difference between plain tap water and distilled water from these public sources.

GIGI KELLETT: Well, there's very little difference. You know, our public water systems go through a very rigorous testing and monitoring system and is tested by the Environmental Protection Agency. So we want to make sure that people know that our public water systems are much better regulated than these bottled water brands, which don't have to go through the same rigorous type of process.

AMY GOODMAN: We're talking to Gigi Kellett, associate campaigns director of Corporate Accountability International. Michael Blanding is a freelance writer, has written the piece "The Bottled Water Lie." Michael, what is the lie?

MICHAEL BLANDING: Well, there are actually several lies, I think, that the bottled water companies perpetrate, but I think the main one is exactly what Gigi said, that this image bolstered by, you know, millions and millions of dollars of advertising that bottled water is somehow better for you, it tastes better, it's more pure. And in many cases, that's simply not true. People are paying, you know, enormous premiums for bottled water and don't even realize the fact that in many cases not only does tap water taste the same, but that it's actually more tightly regulated and actually healthier for you. There have been, you know, several cases of bottled water that's actually been contaminated and found to contain hazardous chemicals. And tap water, there’s actually, you know, a rigorous testing and monitoring of the water supply that actually in many cases makes it healthier.

AMY GOODMAN: When we come back from break, I want to talk about some of those cases of contamination, but also talk about the community struggles that are working to take back their water supply. Our guests are Michael Blanding, wrote "The Bottled Water Lie," and Gigi Kellett of Corporate Accountability International. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We're talking to Gigi Kellett of Corporate Accountability International and Michael Blanding, wrote “The Bottled Water Lie” for alternet.org. They're both in the Boston studio. We're talking about the bottled water lie.

Now, Michael, you begin your piece by talking about Antonia Mahoney. Talk about who she is.

MICHAEL BLANDING: She was someone who was just walking down the street in downtown Boston when the folks at Corporate Accountability -- Gigi and the folks in her group -- were holding something called the Tap Water Challenge, which was a taste test between tap water and various bottled water brands, Aquafina and Dasani. And I stood there during the afternoon and watched, you know, many people come up who were bottled water drinkers and could swear that they could tell the difference and that they could recognize their brand.

And Antonia Mahoney was one of those who -- she actually had given off drinking bottle -- drinking tap water a few years ago and was drinking only Poland Spring and knew, you know, that she would be able to tell Poland Spring of all the other types of water that she was drinking there. And it turned out that what she thought was Poland Spring was actually the tap water from Boston, the good old tap water, which -- we actually have very good tap water that comes from western Mass here. So she was very surprised and shocked and decided right there that she was going to leave off her contract of paying $30 a month for Poland Spring water that she got delivered to her house. So it was very -- and there were other experiences like that during the day that I witnessed.

AMY GOODMAN: Michael, you write about the problems of a suspected carcinogen chemical, bromate. You talk about the contamination of Dasani water, owned by Coca-Cola, in 2004. Explain what the problems are, the contamination issues.

MICHAEL BLANDING: So, ironically, one of the processes that actually takes the tap water and purifies it -- it’s called ozonation -- can actually in some cases have a byproduct, which is bromate, which is, as you say, a suspected carcinogen. And the largest case of contamination was in the UK in 2004, right when Dasani launched in the United Kingdom. They had something like a half-million bottles of Dasani water actually found to be contaminated, and people were getting sick. And, you know, it's just indicative of the lack of controls and the lack of monitoring that you find with bottled water.

And it's not an isolated case. There have been many others that have occurred. Most recently up in Upstate New York with an independent bottled water company, there were multiple cases of bromate contamination, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the issue of filtering? First of all, I don't know if people realize when something says “public water source” that it means tap water. But then, what it means for that tap water to be filtered to -- you talk about additional techniques like reverse-osmosis.

MICHAEL BLANDING: Right, yeah. So there are various techniques that the companies use, and, you know, they tout them as these proprietary techniques that, you know, they go through seven different phases of filtering, and all the rest of it. And, you know, when you look at it, though -- you know, reverse-osmosis is the main one, which is basically just pushing water through a membrane to remove contaminants, and it's actually very similar to the type of process that can be found in home water filters, just, you know, the kind that you attach to your tap for a couple of hundred bucks. So, you know, the -- it's not as sophisticated as they might, you know, pretend that it is.

AMY GOODMAN: And internationally, the movements, from Bolivia to Peru, La Paz, all over.

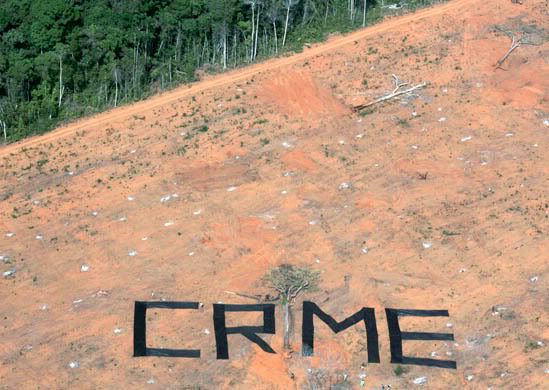

MICHAEL BLANDING: Yeah. What's interesting is that, you know, here in the United States there are, you know, several communities that have actually, you know, had plants take a lot of water from their groundwater up in Michigan, you know, where they can actually see the water level of one of their streams declining because of, you know, the massive amount that Nestle was taking from their water.

And it's even a more critical issue in other countries where water scarcity is a real problem, so places like India, where Coca-Cola and Pepsi have actually, you know, really depleted communities and farmers have been unable to grow their crops, it's kind of been a double whammy. They've taken the water, and then the water that they -- the waste water they've dumped back has been polluted, in many cases. And so, that's one issue, is just the depletion of water from the plants themselves.

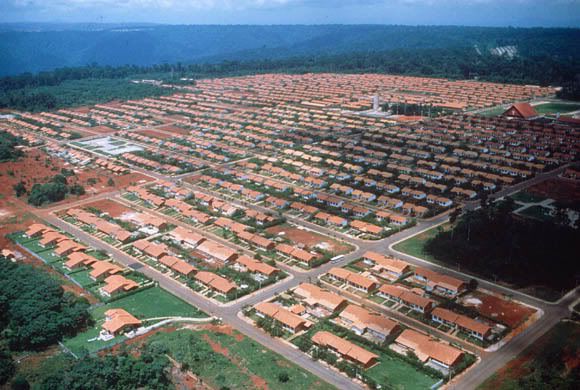

And then the other issue, which I know Gigi could talk about, is just the perception that comes across that somehow tap water is -- you know, municipal water is somehow, you know, not as good as water that's been privatized. And so, you have -- it sort of starts this steady creep of where privatization of water sources becomes OK. And there have been many communities, like in Bolivia, where water supplies have been privatized and have been sold back to -- water that was previously free has, you know, skyrocketed in price. And people have taken to the streets and protested and actually got the private companies to leave.

AMY GOODMAN: Gigi Kellett, let's talk about the tainting of the image of the municipal water supply in this country, the effect of the bottled water advertising industry campaigns.

GIGI KELLETT: Well, this is something that’s of real concern to our organization and our members and activists across the country, because we are seeing this -- you know, who are we turning to to provide our drinking water? And there are -- these bottled water corporations are spending tens of millions of dollars every year on ads that effectively undermine people's confidence in their water. There was actually a poll done by the University of Arkansas earlier this year that found young people tend to choose bottled water over tap water, because they feel it's somehow cleaner or better than their public water systems. And as we've already mentioned here, we know that in reality that's not true. So there is a real concern about the impact that these bottled water corporations are having on the way we think about water.

And our Think Outside the Bottle campaign is aiming to change that, and we're having real success with cities like San Francisco and Ann Arbor, Michigan and New York City, taking a lead on putting their public water systems back in the forefront and not contracting with bottled water corporations, for example, like in Salt Lake City and in San Francisco. And we're seeing restaurants turn to the tap in lieu of bottled water. So there’s a lot that people are starting to look at in terms of this industry and what changes we can make to promote our own public water systems here in this country and make sure that they have the funding they need to thrive, and that also we're looking internationally to make sure that countries that may be cash-strapped also have the resources they need to have good, strong public water systems and not turn to privatization.

AMY GOODMAN: Gigi, tell us about what happened in Salt Lake City and in San Francisco, with the mayor announcing that city money cannot be used to buy bottled water.

GIGI KELLETT: That's right. You know, the mayor of San Francisco, Gavin Newsom, after we had been working with his staff there, working with the San Francisco Department of the Environment and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, they looked at how much money they were spending on bottled water every year. It was close to a half-million dollars. And they said, “We're the forefront. We're cities. We're the forefront of ensuring that people have access to good, safe, clean water. And we're also now at the forefront of dealing with the waste that results from the bottled water industry. So we need to take a stand as a city.” And in June, Mayor Newsom issued an executive order saying that the city would no longer be buying bottled water. And he joined with the mayor of Salt Lake City, Rocky Anderson, and also the mayor of Minneapolis, R.T. Rybak, to put forward a resolution at the US Conference of Mayors calling on a study to really look at what are the impacts of bottled water on our municipal waste. So it’s a real great leadership that we're seeing of these cities.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Gigi, what about the effect that the water in the plastic bottle has? Is there any kind of leeching out? People think that they're getting healthier water in all sorts of ways, but what about the impact of that plastic?

GIGI KELLETT: Well, there are a number of concerns about the impact of the plastic, yes, of course, in the leeching. These bottles that are made are single-serve bottles, so they're not intended to be reused, because of the potential for leeching of the plastic into -- you know, when you're drinking the water. And then, of course, there are the environmental impacts of the bottles that are ending up in our landfills and on the side of the road as litter. They're not being recycled. Only about 23% of these plastic bottles are being recycled. So it's a huge impact for our environment and, of course, for people's health. So we want people to be looking at turning back to the tap and thinking outside the bottle.

AMY GOODMAN: You talked about international, and we're going to go international now to El Salvador.