Life Inc., How The World Became A Corporation And How To Take It Back, by Douglas Rushkoff. The movie:

Then read the book.

Showing posts with label books. Show all posts

Showing posts with label books. Show all posts

Monday, June 01, 2009

Thursday, October 04, 2007

Chris Matthews! Making News!!

Yawn

The Examiner reports:

This is no *new news flash*. We learned this soon during the Scooter Libby trial when, on February 7, 2007, Tim Russert was on the witness stand:

Chris Matthews has written another book, is making the talk show rounds, and is trying to appeal to the left for sales before he crawls back to the right and starts sucking up again so that he can get interviews with them during the election season.

I like to think that venues such as this one on Jon Stewart, where Matthews can't control the conversation, is causing Matthews some introspection into just how responsible he's been for the mess that is the Bush-Cheney administration, by giving Republicans an easy ride these last six years. But then I realize that he said nothing of substance at his book party, and we have no way of knowing which criminality Matthews thinks the administration has been caught in.

The Examiner reports:

Chris Matthews had barely finished praising his colleagues at the 10th anniversary party for his “Hardball” show Thursday night in Washington, D.C. when his remarks turned political and pointed, even suggesting that the Bush administration had "finally been caught in their criminality."

In front of an audience that included such notables as Alan Greenspan, Rep. Patrick Kennedy and Sen. Ted Kennedy, Matthews began his remarks by declaring that he wanted to "make some news" and he certainly didn't disappoint. After praising the drafters of the First Amendment for allowing him to make a living, he outlined what he said was the fundamental difference between the Bush and Clinton administrations.

The Clinton camp, he said, never put pressure on his bosses to silence him.

“Not so this crowd,” he added, explaining that Bush White House officials -- especially those from Vice President Cheney's office -- called MSNBC brass to complain about the content of his show and attempted to influence its editorial content. "They will not silence me!" Matthews declared.

This is no *new news flash*. We learned this soon during the Scooter Libby trial when, on February 7, 2007, Tim Russert was on the witness stand:

2:29 p.m.: All morning, we listened to audio tapes of Scooter Libby's grand jury testimony. Along with yesterday, that makes eight hours of tapes in all. Toward the end of this droning saga, the courtroom gallery was becoming rather sparsely populated.If I didn't know any better, I'd say that Chris Matthews was out hawking another book....Wait a minute, that's exactly what's going on!

But now these tapes are, mercifully, over. We've had our lunch break, and the judge and jury are seated. And for some reason, the courtroom is packed. Some reporters can't even get in. Why?

Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald steps up to the podium. "The government calls Tim Russert," he says.

And there's the man, walking to the witness stand. Or rather, limping to it. Russert is on crutches—the result of a broken ankle. He takes his seat, spells out his name, and describes his job: host of Meet the Press and Washington bureau chief for NBC News.

Fitzgerald launches into questions about a July 2003 phone call Russert received from Scooter Libby. Russert tells us that Libby called him to complain about something Chris Matthews said on his TV show, Hardball. Libby was "agitated," and his voice was "very firm and direct," Russert recounts.

"What the hell's going on with Hardball?" he asked Russert. "Damn it, I'm tired of hearing my name over and over again."

Fitzgerald asks if Russert had ever before, or since, received a call like that from a vice president's chief of staff. Russert says he has not. The call was really just a "viewer complaint." Besides, there was nothing Russert could do about Hardball, since it wasn't his show. He suggested other NBC people that Libby could complain to. And that was the end of the conversation.

Chris Matthews has written another book, is making the talk show rounds, and is trying to appeal to the left for sales before he crawls back to the right and starts sucking up again so that he can get interviews with them during the election season.

"They've finally been caught in their criminality," Matthews continued, although he did not specify the exact criminal behavior to which he referred. He then drew an obvious Bush-Nixon parallel by saying, “Spiro Agnew was not an American hero."

Matthews left the throng of Washington A-listers with a parting shot at Cheney: “God help us if we had Cheney during the Cuban missile crisis. We’d all be under a parking lot.”

Following his remarks, a few network insiders and party goers wondered what kind of effect Matthews' sharp criticism of the White House would have on Tuesday's Republican debate in Dearborn, Michigan, which Matthews co-moderates alongside CNBC's Maria Bartiromo.

"I find it hard to believe that Republican candidates will feel as if they're being given a fair shot at Tuesday's debate given the partisan pot-shots lobbed by Matthews this evening," said one attendee.

When reached, the White House declined to comment and NBC refused requests to release video of the event. The event included such NBC/MSNBC brass as NBC Senior Vice President Phil Griffin (the former "Hardball" executive producer called "Hardball" the "best show on cable television"), "Meet the Press" host Tim Russert, "Today" show executive producer Jim Bell, NBC News Specials Executive Producer Phil Alongi, "Meet the Press" Executive Producer Betsy Fischer, NBC chief foreign affairs correspondent Andrea Mitchell, MSNBC Vice President Tammy Haddad, "Hardball" correspondent David Shuster and Vice President for MSNBC Prime-Time Programming Bill Wolff.

On a side note: Matthews was overheard discussing his Tuesday appearance on "The Daily Show," which featured a heated exchange with host Jon Stewart. According to one source, Matthews was steadfast in his belief that the debate left Stewart crestfallen, and Matthews victorious.

I like to think that venues such as this one on Jon Stewart, where Matthews can't control the conversation, is causing Matthews some introspection into just how responsible he's been for the mess that is the Bush-Cheney administration, by giving Republicans an easy ride these last six years. But then I realize that he said nothing of substance at his book party, and we have no way of knowing which criminality Matthews thinks the administration has been caught in.

Labels:

books,

Bush administration,

Chris Matthews,

Dick Cheney,

free speech,

Jon Stewart

Sunday, September 02, 2007

"Roberts Suggested Miers For The USSC"

That's if you believe that Bush and top aides on his staff would confide in a journalist Bush had just met in December, 2006.

Author of new book out on Bush claims to have inside look at his administration's controversies.

The Washington Post reports:

Rovian prestidigitation.

This looks like misdirection to me. Just in time for Petraeus's and Crocker's return to the U.S. to report on Iraq.

Author of new book out on Bush claims to have inside look at his administration's controversies.

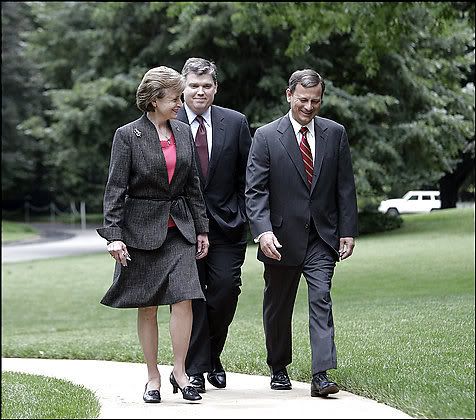

How does the Bush-Cheney administration become inept and indiscreet after more than six years of being the most secretive, disciplined administration in the history of the republic?  Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)

Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)

Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)

Harriet Miers with John G. Roberts Jr., right, and an unidentified person in July 2005. A new book, "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush," describes how Bush came to nominate Miers for the Supreme Court. (By Eric Draper -- The White House Via Getty Images)The Washington Post reports:

John G. Roberts Jr., now the chief justice of the United States, suggested Harriet Miers to President Bush as a possible Supreme Court justice, according to a new book on the Bush presidency.

Miers, the White House counsel and a Bush loyalist from Texas, did not want the job, but Bush and first lady Laura Bush prevailed on her to accept the nomination, journalist Robert Draper writes in "Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush."

Karl Rove, Bush's top political adviser, raised concerns about the selection but was "shouted down" and subsequently muted his objections, while other advisers did not realize the outcry it would cause within the president's conservative political base, Draper writes.

The nomination of Miers was one of several self-inflicted wounds that have damaged the Bush presidency during its second term. After Miers withdrew in the face of the conservative furor, Samuel A. Alito Jr. was selected and confirmed for the seat.

In recounting this and other controversies of Bush's tenure, Draper offers an intimate portrait of a White House racked by more infighting than is commonly portrayed and of a president who would, alternately, intensely review speeches line by line or act strangely disengaged from big issues.

Draper, a national correspondent for GQ, first wrote about Bush in 1998, when he was the Texas governor. He received unusual cooperation from the White House in preparing "Dead Certain," which will hit bookstores tomorrow. In addition to conducting six interviews with the president, Draper said he also interviewed Rove, Vice President Cheney, Laura Bush and many senior White House and administration officials.

Draper writes that Bush was "gassed" after an 80-minute bike ride at his Crawford, Tex., ranch on the day before Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast and was largely silent during a subsequent video briefing from then-FEMA director Michael D. Brown and other top officials making preparations for the storm.

He also reports that the president took an informal poll of his top advisers in April 2006 on whether to fire Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

During a private dinner at the White House to discuss how to buoy Bush's presidency, seven voted to dump Rumsfeld, including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, incoming chief of staff Joshua B. Bolten, the outgoing chief, Andrew Card, and Ed Gillespie, then an outside adviser and now White House counselor. Bush raised his hand along with three others who wanted Rumsfeld to stay, including Rove and national security adviser Stephen J. Hadley. Rumsfeld was ousted after the November elections.

The book offers more than 400 footnotes, but Draper does not make clear the sourcing for some of the more arresting assertions -- such as the one about Roberts's role in the Miers nomination, which has hitherto not come to light. Roberts's nomination was highly praised by conservatives, and they criticized Miers as lacking conservative credentials.

White House spokesman Tony Fratto said yesterday that he had no comment on the book, including the claim about the Miers nomination. Roberts could not be reached for comment, a Supreme Court spokeswoman said last night.

Draper offers some intriguing details about Bush's personal habits, such as his intense love of biking. He reports that White House advance teams and the Secret Service "devoted inordinate energy to satisfying Bush's need for biking trails," descending on a town a couple of days before the president's arrival to find secluded hotels and trails the boss would find challenging.

He also makes new disclosures about the behind-the-scenes infighting at the White House that helped prompt the change from Card to Bolten in the spring of 2006. By that point, he reports, some close to the president had concluded that "the White House management structure had collapsed," with senior aides Rove and Dan Bartlett "constantly at war."

He quotes Gillespie as telling one Republican while running interference for Alito's Supreme Court nomination: "I'm going crazy over here. I feel like a shuttle diplomat, going from office to office. No one will talk to each other."

It has been previously reported that Card first suggested he be replaced to help rejuvenate the White House. But Draper writes that Bush settled on Bolten, then director of the Office of Management and Budget, as the new chief of staff before telling Card. When Card congratulated Bolten on his new assignment, he writes, Bolten "could tell that Card was somewhat surprised and hurt that Bush had moved so swiftly to select a replacement."

Rove, meanwhile, was not happy, Draper writes, with Bolten's decision to strip him of his oversight of policy at the White House, directing his focus instead to politics and the coming midterm elections. Bolten noticed that other staffers were "intimidated" by Rove, and Rove was seen as doing too much, "freelancing, insinuating himself into the message world . . . parachuting into Capitol Hill whenever it suited him."

Draper's book also tackles the run-up to the 2000 election and the administration's handling of Iraq.

He writes that Rove told Bush it was a bad idea to select Cheney as his vice president: "Selecting Daddy's top foreign-policy guru ran counter to message. It was worse than a safe pick -- it was needy." But Bush did not care -- he was comfortable with Cheney and "saw no harm in giving his VP unprecedented run of the place."

Draper offers little additional insight or details of Cheney's large influence in administration policy. But he writes that, despite his air of unflappability, the vice president did find himself ruminating over mistakes made, chief among them installing L. Paul Bremer and the Coalition Provisional Authority to run Iraq for a year after the invasion. Instead, Draper suggests, Cheney believes that the White House should have set up a provisional government right away, as Ahmed Chalabi's Iraqi National Congress recommended from the beginning.

Several of Bush's top advisers believe that the president's view of postwar Iraq was significantly affected by his meeting with three Iraqi exiles in the Oval Office several months before the 2003 invasion, Draper reports.

He writes that all three exiles, Kanan Makiya, Hatem Mukhlis and Rend Franke, agreed without qualification that "Iraq would greet American forces with enthusiasm. Ethnic and religious tensions would dissolve with the collapse of Saddam's regime. And democracy would spring forth with little effort -- particularly in light of Bush's commitment to rebuild the country."

Rove assured Bush, Draper reports, that he had known nothing about Valerie Plame, a CIA operative whose covert status was revealed by administration officials to reporters after Plame's husband criticized the administration's case for war in Iraq. "When Bush learned otherwise," he said, "he hit the roof."

Bush considered whether to cooperate with the book for several months, Draper reports. The two men met for the first time on Dec. 12, 2006, and at the conclusion, the president agreed to another interview. In one of the interviews, he looked ahead to his looming post-presidency, talking of his plans to build an institute focused on freedom and to "replenish the ol' coffers" by giving paid speeches.

He told Draper he could see himself shuttling between Dallas and Crawford. Noting that he ran into former president Bill Clinton at the United Nations last year, Bush added, "Six years from now, you're not going to see me hanging out in the lobby of the U.N."

Rovian prestidigitation.

This looks like misdirection to me. Just in time for Petraeus's and Crocker's return to the U.S. to report on Iraq.

Wednesday, August 08, 2007

Out of Sight, Out of Mind?

The Loss of Privacy in America

There are 4.2 million closed-circuit TV cameras spying on people as they go about their lives in Great Britain. Cities around America are following Great Britain's lead in watching people's every move. At what cost?

In The Washington Times, former Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia Bob Barr writes:

Jeffrey Rosen, an associate professor at GWU Law School and whom you also may recall from his testimony on one of the panels that testified at Clinton's impeachment, wrote a book entitled, "The Unwanted Gaze: The Destruction of Privacy in America."

In it, he talks about a doctrine in Jewish law, "hezzek re'iyyah," which means "the injury caused by seeing." He quotes the Encyclopedia Talmudit:

Just because people don't want to be observed doesn't mean they are engaged in criminal acts or "wrongdoing." And a state that insists that it has the right to determine if that is so, loses the very traits that set the American people apart from others - Our creativity and ingenuity. Innovation requires being able to make mistakes, trial and error, practice, out of the watch of prying and judgmental eyes.

There are 4.2 million closed-circuit TV cameras spying on people as they go about their lives in Great Britain. Cities around America are following Great Britain's lead in watching people's every move. At what cost?

In The Washington Times, former Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia Bob Barr writes:

Though the lion's share of publicity surrounding Tony Blair's recent departure as Britain's prime minister focused on his legacy as George W. Bush's top foreign cheerleader, a more lasting legacy for Mr. Blair's lengthy tenure as Britain's chief "decider" will be that he greatly accelerated Great Britain's ascendancy to the position of the "most surveilled" society in the world. Still, Michael Bloomberg, the Democrat-turned-Republican-turned-independent mayor of New York is giving Mr. Blair a run for the money as the most surveillance-hungry public official in the world.

Even though officials in other cities are embracing and installing surveillance cameras in huge numbers — Chicago, Detroit and Washington, D.C., to name a few — the latest plan unveiled by Mr. Bloomberg and his equally surveillance-enamored police commissioner, Raymond Kelly, leaves these other American cities in the surveillance dust. Truly what we are witnessing being created here is a 21st-century Panopticon.

The Panopticon, as envisaged by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), was a society (initially proposed as a prison) in which surreptitious surveillance of the citizenry was always possible and ever-known. Control was exercised not by being surveilled continuously but by each person knowing they might be under surveillance at any time, or all the time.

Bentham was a man ahead of his time. His pet project was never fully carried out because the technology available at the time, relying as it did on direct, physical surveillance (electricity as a harnessable force, with which Benjamin Franklin was just then beginning to experiment, was still more than a century away) made creation of a workable Panopticon infeasible. Were Bentham alive today, he probably would be the most sought-after consultant on the planet.

The key to the surveillance society foreseen by Bentham more than two centuries ago was control. Crime was rampant in late 18th-century and early 19th-century London. Controlling the populace by modifying behavior became the central problem for Bentham and other social scientists of the day.

Of course, the notion that surveillance is key to control was not new with Bentham; centuries before, the Greek philosopher Plato had mused about the power of the government to control through surveillance, when he raised the still-relevant question, "Who watches the watchers?"

More recently, of course, George Orwell gave voice to the innate fear that resides deep in many of our psyches against government surveillance, in his nightmare, "Big Brother is Watching You" world of the novel "1984."

Whether in Bentham's world, or Plato's or Orwell's, the central task is to modify behavior by convincing people that the government — that entity with power over their lives — may be watching them all the time or at any particular time. As 20th-century American philosopher and advocate of personal freedom Ayn Rand noted, taking away a person's privacy renders to the government the ability to control absolutely that person.

In fact, studies by Bentham and others have established that individuals do in fact modify their behavior if they believe they are being watched by authorities.

Whether learned of these philosophical treatises or not, Mayor Bloomberg and former Prime Minister Blair epitomize the almost mindless, unquestioning embrace of surveillance as the solution to problems — real, manufactured or exaggerated — that pervades government post-September 11, 2001. Fear of terrorism as much as fear of crime is the currency by which government at all levels convinces a fearful populace that a surveilled society is a safe society.

Of course, Messrs. Bloomberg and Blair have one benefit available to them that was largely denied Bentham — money. Lots of money. "Homeland security" money taken from the wallets of taxpayers, but treated by government appropriators as theirs by right, is eagerly ladled out for cameras to surveill all. Add the magic words "for fighting terrorism" to your request for federal money and the chances of securing those dollars are made many times greater.

Not only is money readily available for government agencies to install, monitor and expand surveillance systems, but the cameras themselves are magnificent generators of money. Already in London, vehicle owners are billed for using their cars and trucks in certain areas and at certain times, through use of surveillance cameras that photograph, record and track vehicle license plates. The multimillion-dollar system being set up by Mayor Bloomberg and Commissioner Kelly will almost certainly be similarly employed down the road.

With more than 4.2 million closed-circuit television surveillance cameras now operating in Great Britain (the vast majority in and around London), Mr. Bloomberg has a long way to catch up to his British counterparts. Yet the eagerness with which he is approaching this challenge, coupled with the easy money available to him and a largely ignorant and compliant citizenry willing to surrender their privacy in the vain hope that thousands of surveillance cameras will guarantee their safety, bodes well for the Gotham City to overtake London as the most surveilled city on the planet. Somewhere, Jeremy Bentham is smiling; and George Orwell is saying, "I told you so."

Jeffrey Rosen, an associate professor at GWU Law School and whom you also may recall from his testimony on one of the panels that testified at Clinton's impeachment, wrote a book entitled, "The Unwanted Gaze: The Destruction of Privacy in America."

In it, he talks about a doctrine in Jewish law, "hezzek re'iyyah," which means "the injury caused by seeing." He quotes the Encyclopedia Talmudit:

"Even the smallest intrusion into private space by the unwanted gaze causes damage, because the injury caused by seeing cannot be measured."The loss of privacy, our right to an interior experience where we rehearse ideas and innovation away from judgment and interference, has had a devastating impact on our culture.

Jewish jurisprudence of the Middle Ages provided for a legal action to stop a neighbor from building a window from which he could peer into your courtyard.

Just because people don't want to be observed doesn't mean they are engaged in criminal acts or "wrongdoing." And a state that insists that it has the right to determine if that is so, loses the very traits that set the American people apart from others - Our creativity and ingenuity. Innovation requires being able to make mistakes, trial and error, practice, out of the watch of prying and judgmental eyes.

Labels:

American culture,

Bob Barr,

books,

Fourth Amendment,

Great Britain,

Michael Bloomberg,

New York,

privacy,

video

Monday, August 06, 2007

Beyond Disaster

Chris Hedges, the former Middle East bureau chief for The New York Times, spent seven years in the Middle East. He was part of the paper’s team of reporters who won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for coverage of global terrorism. He is the author of “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.” His latest book is “American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America.”

For TruthDig, Chris Hedges writes:

Yet nobody calls this President to account. Nobody confronts him with the truths from on the ground, from those not beholden to him, in his line of command.

Bush hasn't had a full court press conference in almost a year. The White House press corps is content to be spun by an assistant press secretary, dutifully writing down her alliterative cliches, and repeating them back into microphones for the evening news.

And the beat goes on.

For TruthDig, Chris Hedges writes:

The war in Iraq is about to get worse—much worse. The Democrats’ decision to let the war run its course, while they frantically wash their hands of responsibility, means that it will sputter and stagger forward until the mission collapses. This will be sudden. The security of the Green Zone, our imperial city, will be increasingly breached. Command and control will disintegrate. And we will back out of Iraq humiliated and defeated. But this will not be the end of the conflict. It will, in fact, signal a phase of the war far deadlier and more dangerous to American interests.

Iraq no longer exists as a unified country. The experiment that was Iraq, the cobbling together of disparate and antagonistic patches of the Ottoman Empire by the victorious powers in the wake of World War I, belongs to the history books. It will never come back. The Kurds have set up a de facto state in the north, the Shiites control most of the south and the center of the country is a battleground. There are 2 million Iraqis who have fled their homes and are internally displaced. Another 2 million have left the country, most to Syria and Jordan, which now has the largest number of refugees per capita of any country on Earth. An Oxfam report estimates that one in three Iraqis are in need of emergency aid, but the chaos and violence is so widespread that assistance is impossible. Iraq is in a state of anarchy. The American occupation forces are one more source of terror tossed into the caldron of suicide bombings, mercenary armies, militias, massive explosions, ambushes, kidnappings and mass executions. But wait until we leave.

It was not supposed to turn out like this. Remember all those visions of a democratic Iraq, visions peddled by the White House and fatuous pundits like Thomas Friedman and the gravel-voiced morons who pollute our airwaves on CNN and Fox News? They assured us that the war would be a cakewalk. We would be greeted as liberators. Democracy would seep out over the borders of Iraq to usher in a new Middle East. Now, struggling to salvage their own credibility, they blame the debacle on poor planning and mismanagement.

There are probably about 10,000 Arabists in the United States—people who have lived for prolonged periods in the Middle East and speak Arabic. At the inception of the war you could not have rounded up more than about a dozen who thought this was a good idea. And I include all the Arabists in the State Department, the Pentagon and the intelligence community. Anyone who had spent significant time in Iraq knew this would not work. The war was not doomed because Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz did not do sufficient planning for the occupation. The war was doomed, period. It never had a chance. And even a cursory knowledge of Iraqi history and politics made this apparent.

This is not to deny the stupidity of the occupation. The disbanding of the Iraqi army; the ham-fisted attempt to install the crook and, it now turns out, Iranian spy Ahmed Chalabi in power; the firing of all Baathist public officials, including university professors, primary school teachers, nurses and doctors; the failure to secure Baghdad and the vast weapons depots from looters; allowing heavily armed American units to blast their way through densely populated neighborhoods, giving the insurgency its most potent recruiting tool—all ensured a swift descent into chaos. But Iraq would not have held together even if we had been spared the gross incompetence of the Bush administration. Saddam Hussein, like the more benign dictator Josip Broz Tito in the former Yugoslavia, understood that the glue that held the country together was the secret police.

Iraq, however, is different from Yugoslavia. Iraq has oil—lots of it. It also has water in a part of the world that is running out of water. And the dismemberment of Iraq will unleash a mad scramble for dwindling resources that will include the involvement of neighboring states. The Kurds, like the Shiites and the Sunnis, know that if they do not get their hands on water resources and oil they cannot survive. But Turkey, Syria and Iran have no intention of allowing the Kurds to create a viable enclave. A functioning Kurdistan in northern Iraq means rebellion by the repressed Kurdish minorities in these countries. The Kurds, orphans of the 20th century who have been repeatedly sold out by every ally they ever had, including the United States, will be crushed. The possibility that Iraq will become a Shiite state, run by clerics allied with Iran, terrifies the Arab world. Turkey, as well as Saudi Arabia, the United States and Israel, would most likely keep the conflict going by arming Sunni militias. This anarchy could end with foreign forces, including Iran and Turkey, carving up the battered carcass of Iraq. No matter what happens, many, many Iraqis are going to die. And it is our fault.

The neoconservatives—and the liberal interventionists, who still serve as the neocons’ useful idiots when it comes to Iran—have learned nothing. They talk about hitting Iran and maybe even Pakistan with airstrikes. Strikes on Iran would ensure a regional conflict. Such an action has the potential of drawing Israel into war—especially if Iran retaliates for any airstrikes by hitting Israel, as I would expect Tehran to do. There are still many in the U.S. who cling to the doctrine of pre-emptive war, a doctrine that the post-World War II Nuremberg laws define as a criminal “war of aggression.”

The occupation of Iraq, along with the Afghanistan occupation, has only furthered the spread of failed states and increased authoritarianism, savage violence, instability and anarchy. It has swelled the ranks of our real enemies—the Islamic terrorists—and opened up voids of lawlessness where they can operate and plot against us. It has scuttled the art of diplomacy. It has left us an outlaw state intent on creating more outlaw states. It has empowered Iran, as well as Russia and China, which sit on the sidelines gleefully watching our self-immolation. This is what George W. Bush and all those “reluctant hawks” who supported him have bequeathed us.

What is terrifying is not that the architects and numerous apologists of the Iraq war have learned nothing, but that they may not yet be finished.

Yet nobody calls this President to account. Nobody confronts him with the truths from on the ground, from those not beholden to him, in his line of command.

Bush hasn't had a full court press conference in almost a year. The White House press corps is content to be spun by an assistant press secretary, dutifully writing down her alliterative cliches, and repeating them back into microphones for the evening news.

And the beat goes on.

Monday, April 16, 2007

Book Bin: "Oil on the Brain," by Lisa Margonelli

Americans buy 10,000 gallons of gasoline a second, but few of us know how oil is created and drilled, how gas stations compete or what actually goes on in a refinery—let alone what happens in the mysterious Strategic Petroleum Reserve, where the U.S. government stores roughly 700 million barrels of oil in underground salt caverns on the Gulf Coast of Texas.

Author Lisa Margonelli’s desire to learn took her on a one-hundred thousand mile journey from her local gas station to oil fields half a world away. In search of the truth behind the myths, she wriggled her way into some of the most off-limits places on earth: the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the New York Mercantile Exchange’s crude oil market, oil fields from Venezuela, to Texas, to Chad, and even an Iranian oil platform where the United States fought a forgotten one-day battle.

In the summer of 2003, she started hanging out at independent gas stations, where owners might clear pennies per gallon of gas, surviving on impulse sales of junk food and soda. Her journey takes us up the delivery chain, spending a typical day with a tanker truck driver, hanging out with suppliers, touring refineries, and seeing what life is like at an oil rig. Whether visiting "wildcatters" in Texas, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve in the Gulf of Mexico, or the oil pit at the New York Mercantile Exchange, Margonelli charms her way into the good graces of insiders to report on the vast petroleum network. Her voyage takes us to Venezuela, Chad (whose villagers who are said to wander the oil fields in the guise of lions), Nigeria (where a Nigerian warlord who changed the world price of oil with a single cell phone call), China (where Shanghai bureaucrats dream of creating a new Detroit) and ultimately the Persian Gulf, where she spends time at the Salmon oil fields in Iran. Filled with rich history, industry anecdotes, and politics, Margonelli's book brings a deeper appreciation of the complicated and often tenuous process that we take for granted.

Excerpt:

Chapter 1 - GAS STATION: Chasing The Hidden Penny

Regular Unleaded $1.61 9/10

Twin Peaks Petroleum sits at a welcoming angle to a busy San Francisco intersection. On this morning in the summer of 2003, a thick fog has crawled over the station, folding each of the eight drivers standing at the pumps in an envelope of cold mist. At the back of the lot sits a garage where a small convenience store glows. On the storefront is a poster of an ebullient snowman clutching a cola, while icicle letters drip the words COLD POP over his head. Inside the convenience store, among the security cameras and parabolic mirrors, the Doritos, cigarettes, and Snapples, jammed into a space no larger than a postal truck, a tall man with dark circles under his eyes appears to doze. His eyelids hang low, twitching; he mumbles; he moves with excruciating deliberation as he counts change.[For more, you'll have to get the book.]

I am leaning against a shelf holding several grades of motor oil, individually wrapped strawberry cheesecake muffins, and four flavors of corn nuts: picante, regular, nacho cheese, and ranch. I am no more lively than B. J., the droopy manager. And I am recording the flavors of corn nuts in my notebook to stay awake. “Corn Gone Wrong” say the packages. I record that too. I’ve come to the gas station to watch Americans buy gasoline, as a way of understanding how we fit into the trillion–dollar world oil economy. But now that I’m here, I realize I’ve been here before, bought gas so many times myself I feel there’s nothing to see. The fumble, the stuporous swipe of the card, the far–off look: I know them well. Gas stations are everywhere, but when you’re in one, you’re nowhere in particular. Icicle letters are taking shape in my head: WHAT DID YOU EXPECT?

I keep writing: Trojan spermicidally lubricated snugger fit, two Sominex and a folded paper cup, phone cards, batteries, air fresheners printed to look like ice cream sundaes, a greeting card with a picture of a pansy and the words “You’re too nice to be sick.” The customers standing out at the pumps have a preoccupied, anxious look—could they be distracted enough to buy a card that says “You’re too nice to be sick”?

Gas stations are collections of incidental items, impulses, and routines that seem in themselves to be inconsequential but aggregate into a goliath economy when multiplied by the hungers of 194 million licensed American drivers. Corn nuts, for example, are part of $4.4 billion in salty snacks sold at gas station convenience stores yearly, nearly all impulse buys. The hopeful purchase $25 billion in lottery tickets. People with the sniffles spent $323 million on cold medicine at gas stations in 2001. And the faint smell of gasoline near the pumps? In California alone, the amount of gasoline vapor wafting out of stations, as we fill our cars, totals 15,811 gallons a day—roughly the equivalent of two full tanker trucks (1). In the gas station, we’ve collaborated to create a culture of speed, convenience, low prices, and 64–ounce cup holders, which allow us to express what the industry calls our “passion for fountain drinks.” Japanese auto executives have hired American anthropologists to explain the mystery of why the purchase of a $40,000 car hangs on the super–sizing of the cup holder.

And then there is the gasoline: 1,143 gallons per household per year, purchased in two–and–a–half–minute dashes. We make 16 billion stops at gas stations yearly, taking final delivery on 140 billion gallons of gasoline that has traveled around the world in tanker ships, pipelines, and shiny silver trucks. And then we peel out, get on with our real lives, get back on the highway, or go find a restroom that’s open, for Pete’s sake.

With a wave of our powerful credit cards, American drivers buy one-ninth of the world’s crude oil production per day. That makes us elephants in the global oil economy–our needs are felt around the world, from the tiniest villages in Africa, the Amazon, and the Arctic, to the highest towers in Vienna, Riyadh, and New York. When we lick our lips, they open their taps. When we are in a funk, their governments fall. Here in front of the pump, surrounded by buntings in the joyful colors of children’s birthday party balloons, we have the opportunity to be our truest selves in the great, over–the–top drama/business that is the world oil supply chain.

But as you know, buying gas can be done by the living dead. Swipe card, insert nozzle, punch the button with the greasy sheen: Gasoline flows into the tank while money flows out of the bank account. Filling a car seems less like making a purchase than a ritual, a formality that isn’t quite real.

It’s not even clear what we’re buying—gasoline’s fantastic uniformity means one is as good as another. Water doesn’t mix with gas, so beyond occasional traces of vapor, we don’t even have to worry about buying substandard gasoline. And all traces of where the fuel came from are completely erased by the time it gets to a gas pump. Texaco gasoline is no longer from Texas, and gas from Unocal is not from “Cal.” Both companies have been purchased by Chevron, anyway. If gasoline were coffee, we might believe the Baku blend offered a fast but mellow ride.

As if acknowledging the futility of trying to stand out from the pack when 168,987 gas stations are selling essentially an identical chemical mix, stations have adopted a clannish ugliness. Whether they’re in Fairbanks, Alaska, or Pine Island, Florida, they all subscribe to the familiar topography of canopied islands, cheerful plate glass, struggling hedges, and “Smile. You’re being watched by a surveillance camera” signs. Predictable they are, to the very last 9/10ths of a cent, which is permanently printed on every last gas price sign in the land.

The gas station’s blandness is misleading, though. Hidden in its windows, pumps, and hedges are clues to the true nature of the American bargain with gasoline and the enigma of its role in the world.

On the counter in front of B. J. stands a line of purple plastic wizards, stomachs filled with green candy pebbles. Their shiny eyes stare at me expectantly.

At the periphery of my vision, a van enters Twin Peaks yard and parks near the fence. In the time it takes the door to slam, B. J. grows a foot taller, loses his paunch, and becomes a man of action. He snaps the countertop open, bounces into the yard, and lands in front of the van driver in one tigerlike swoop. Words are exchanged. The driver sulkily returns to his van and B. J. returns to the store, shaking his head. People try to ditch their cars in the station and take the bus, he explains, taking his position behind the wizards. “The customer is always right,” says B. J., “but bad people going round.”

Like vapors, bad people always seem to be wafting through the gas station. Last week B. J. ran out to stop a truck that was barreling toward the station’s lighted canopy. The truck driver ignored him and crunched the canopy. Cars have driven willy nilly through the hedges as he watched. Nightly, people break through the chains on the four entrances. Once he found a gun in the hedge, stashed by a kid on the way to juvenile court. His response? Shave the hedges. Every morning he cleans up garbage, cans, and bottles filled with things we won’t discuss. Daily, and constantly, people try to steal: window squeegees, sodas, condoms, money, and phone calls. Behind B. J.’s head are the counterfeit $20 bills the station has intercepted.

People use elaborate schemes to steal gas, he explains. Sometimes they’ll pay for $5 and shut the pump off when it reaches $4.75. Then they return to the clerk, telling him to turn the pump back on, knowing that the pumps don’t turn off after dispensing amounts less than a dollar. Then they fill their tank and drive off. Others play on the sympathies of the attendant or accuse him of trying to cheat them. In stations where people pump before they pay, they often just drive off. The average gas station loses more than $2,141 a year to gasoline theft. Some lose much more.

Think of a gas station as a crime scene before the fact, and you’ll start to appreciate it as a maze engineered for belligerent rats. Hedges, which I’d interpreted as a pathetic attempt at dignity and baronial pretensions, actually eliminate escape routes for would–be robbers, limiting holdups. Many convenience stores buy “target hardening” kits, which include decals imprinted with rulers so that clerks can tell the police how tall the robbers were, two stickers that say “No 20s, no 50s,” two “Thank You” decals, and one “Smile. You are being watched by our video security.”

Even so, crime is always evolving. “After we did target hardening in stores in the 1980s, the crime moved to the pumps—carjackings and abductions,” says Dr. Rosemary Erickson, a sociologist who’s studied gas station crime for thirty years. “Now it’s public nuisance crimes in the parking lots. Gas stations are considered a magnet.” (2) Nearly nine percent of U.S. robberies happen in gas stations and convenience stores, and the average gas station lost $1,749 to robbery in 2004.

Some of the crimes are not about money at all; they’re about freefloating anger. When gas prices are high, more people get “pump rage” and try to drive off without paying for gas. The Indian and Pakistani immigrants who own and staff many stations bear the brunt. After 9/11, people who were angry at some vague combination of OPEC and Osama bin Laden attacked a hundred clerks at 7–Eleven gas stations and convenience stores in a month. Five men were killed for looking “Middle Ea...

Friday, January 26, 2007

Our Mercenaries in Iraq: Blackwater Inc and Bush's Undeclared Surge

Is Bush out to further outsource war?

The private security firm Blackwater USA is back in the news again. On Tuesday, hours before President Bush’s State of the Union address, one of the Blackwater’s helicopters was brought down in a violent Baghdad neighborhood. Five Blackwater troops - all Americans - were killed. Reports say the men’s bodies show signs of execution-style deaths with bullet wounds to the back off the head.

Blackwater provided no identities or details of those killed. They did release a statement saying the deaths “are a reminder of the extraordinary circumstances under which our professionals voluntarily serve to bring freedom and democracy to the Iraqi people.”

President Bush made no mention of the incident during his State of the Union. But he did address the very issue that has brought dozens of private security companies like Blackwater to Iraq in the first place: the need for more troops.

Amy Goodman of Democracy Now! talks with Jeremy Scahill, a Puffin Foundation Writing Fellow at The Nation Institute and author of, “Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army”:

The private security firm Blackwater USA is back in the news again. On Tuesday, hours before President Bush’s State of the Union address, one of the Blackwater’s helicopters was brought down in a violent Baghdad neighborhood. Five Blackwater troops - all Americans - were killed. Reports say the men’s bodies show signs of execution-style deaths with bullet wounds to the back off the head.

Blackwater provided no identities or details of those killed. They did release a statement saying the deaths “are a reminder of the extraordinary circumstances under which our professionals voluntarily serve to bring freedom and democracy to the Iraqi people.”

President Bush made no mention of the incident during his State of the Union. But he did address the very issue that has brought dozens of private security companies like Blackwater to Iraq in the first place: the need for more troops.

Amy Goodman of Democracy Now! talks with Jeremy Scahill, a Puffin Foundation Writing Fellow at The Nation Institute and author of, “Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army”:

AMY GOODMAN: President Bush made no mention of the incident during his State of the Union, but he did address the very issue that’s brought dozens of private security companies like Blackwater to Iraq in the first place: the need for more troops.

PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH: Tonight, I ask the Congress to authorize an increase in the size of our active Army and Marine Corps by 92,000 in the next five years. A second task we can take on together is to design and establish a volunteer civilian reserve corps. Such a corps would function much like our military reserve. It would ease the burden on the Armed Forces by allowing us to hire civilians with critical skills to serve on missions abroad when America needs them.

AMY GOODMAN: Is the President looking to further outsource war? My next guest writes, “Blackwater is a reminder of just how privatized the Iraq war has become.” Jeremy Scahill is a Puffin Foundation Writing Fellow at the Nation Institute. He’s author of the forthcoming book Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army. He has an op-ed piece in yesterday's Los Angeles Times, entitled "Are Mercenaries in Iraq?" Joining us now in the firehouse studio, welcome to Democracy Now!, Jeremy.

JEREMY SCAHILL: It’s good to be home.

AMY GOODMAN: We invited Blackwater on; they refused. But, Jeremy, let's talk fist about Blackwater. What is it?

JEREMY SCAHILL: Blackwater is a company that began in 1996 as a private military training facility in -- it was built near the Great Dismal Swamp of North Carolina. And visionary executives, all of them former Navy Seals or other Elite Special Forces people, envisioned it as a project that would take advantage of the anticipated government outsourcing.

Well, here we are a decade later, and it’s the most powerful mercenary firm in the world. It has 20,000 soldiers on the ready, the world’s largest private military base, a fleet of twenty aircraft, including helicopter gunships. It’s become nothing short of the Praetorian Guard for the Bush administration's so-called global war on terror. And it’s headed by a very rightwing Christian activist, ex-Navy Seal named Erik Prince, whose family was one of the major bankrollers of the Republican Revolution of the 1990s. He, himself, is a significant funder of President Bush and his allies.

And what they’ve done is they have built a very frightening empire near the Great Dismal Swamp in North Carolina. They’ve got about 2,300 men actively deployed around the world. They provide the security for the US diplomats in Iraq. They’ve guarded everyone, from Paul Bremer and John Negroponte to the current US ambassador, Zalmay Khalilzad. They’re training troops in Afghanistan. They have been active in the Caspian Sea, where they set up a Special Forces base miles from the Iranian border. They really are the frontline in what the Bush administration viewed as a necessary revolution in military affairs. In fact, they represent the life's work of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, the “life's work”?

JEREMY SCAHILL: Well, Dick Cheney, when he was Defense Secretary under George H.W. Bush during the Gulf War, one of the last things he did before leaving office was to create an unprecedented lucrative market for the firm that he would go on to head, Halliburton. He commissioned [a] Halliburton [division] to do a study on how to privatize the military bureaucracy. That effectively created the groundwork for the absolute war profiteer bonanza that we’ve seen unfold in the aftermath of 9/11. I mean, Clinton was totally on board with all of this, but it has exploded since 9/11. And so, Cheney, after he left office, when the first Bush was the president, went on to work at the neoconservative American Enterprise Institute, which really led the push for privatization of the government, not just the military.

And then, when these guys took office, Rumsfeld's first real major address, delivered on September 10, 2001, he literally declared war on the Pentagon bureaucracy and said he had come to liberate the Pentagon. And what he meant by that -- and he wrote this in an article in Foreign Affairs -- was that governments, unlike companies, can't die. He literally said that. So you have to figure out new incentives for competition, and Rumsfeld said that it should be run more like a corporation than a bureaucracy. And so, the company that most embodies that vision -- and they call it a revolutionary in military affairs. It’s a total part of the Project for a New American Century and the neoconservative movement. The company that most embodies that is not Halliburton; it’s Blackwater.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what you understand happened on Tuesday: President Bush giving his address, the Blackwater helicopter crashing.

JEREMY SCAHILL: Well, I think a lot of people -- even though I think there’s been a lot of reporting on it and it’s been out in the public sphere, I think a lot of people still would be surprised to know that the US ambassador in Iraq and US diplomats throughout Iraq and US diplomatic facilities and regional occupational offices are actually guarded by mercenaries. And Blackwater has a $300 million contract to provide diplomatic security. And so, they guard Zalmay Khalilzad and other US diplomats in Iraq.

While what we understand -- and, of course, as you know, reports are always very shaky in the early stages -- is that a US diplomatic convoy came under fire in a Sunni neighborhood of Baghdad, and a Blackwater helicopter apparently landed to try to respond to that attack, because Blackwater and its “Little Bird” helicopters provide the security for diplomatic convoys, and they got engaged in some kind of a firefight on the ground, and four men from one helicopter were killed. Then another helicopter responded and was brought down, either by fire or it got tangled in some wires.

Four of the five men who worked for Blackwater that were killed were shot in the back of the head, according to reports. And what’s interesting about this is that Zalmay Khalilzad said that he had traveled with the men and then said that he had gone to the morgue to view their bodies. And he said that the circumstances of their death were unclear, because of what he called the “fog of war.” But I think it’s very possible that they were guarding a very senior diplomat, if not Zalmay Khalilzad himself. I mean, we don't have evidence to suggest that, but the fact that Khalilzad really came out forward and said, These were fine men. I was with them and visited them in the morgue, indicates that it could have been a very serious attack on a senior official.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you think is the actual body count in Iraq of US soldiers? I mean, we count them very carefully, you know, when it surpassed 3,000. This was extremely significant. What really is the number of US military dead?

JEREMY SCAHILL: Military dead is -- I mean, I think it’s interesting, because the lines have totally been erased. I would say that we should be counting the deaths of Blackwater soldiers in the total troop count. I mean, I filed over the last year a lot of Freedom of Information Act requests, and one of the ways that we have found to discover the deaths of the number of contractors that have been killed is actually through the Department of Labor, because the government has a federal insurance scheme that’s been set up, which is actually very controversial -- grew out of something called the Defense Base Act -- and it’s insurance provided to contractors who service the US military abroad. And so, as of late last year, more than 600 families of contractors in Iraq had filed for those benefits.

So I think we’re talking somewhere in the realm of -- and these are just US contractors that have rights to federal benefits inside of the United States. Remember, it’s not necessarily Americans that make up the majority of these 100,000 -- 100,000 -- contractors that are operating in Iraq right now, 48,000 of whom are mercenaries, according to the GAO. So I don't think it’s possible to put a fine point on the number of troops killed, because the Bush administration has found a backdoor way to engage in an undeclared expansion of the occupation by deploying these private armies.

And at the State of the Union address the other night, Bush announces this civilian reserve corps, which is gaining momentum among Democrats and others. Wesley Clark has talked about it, the former presidential candidate and Supreme Allied NATO Commander. But what that is is another Frankenstein scheme that Cheney and these guys cooked up in their outsourcing laboratory to engage in an undeclared expansion. I mean, on the one hand, we have Bush talking about an official US troop surge. The Army said -- a few months ago, when Colin Powell said that the active-duty Army is basically broken, the Army was calling for 30,000 troops over ten years. Bush then announces in his State of the Union 92,000 active-duty troops over five years, and at the same time, they're increasing the presence of the mercenaries, increasing the presence of the other contractors, talking about some privatized or civilian reserve corps. This is all an undeclared expansion of the US occupation, totally against the will of the American people and the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Civilian reserve corps?

JEREMY SCAHILL: Right. That's what they're calling it. And, you know, I mean, a lot of what has been tossed around about this since 2002 has been envisioning a sort of disaster response, international aid. You know, it’s all very benign-sounding, but the context of it, when Bush announced it the other night, he said we need 92,000 troops and we should develop a civilian reserve corps to supplement the work of the military.

Now, what’s interesting, Amy, is that two years ago Erik Prince, the head of Blackwater USA, was speaking at a military conference. He only comes out of his headquarters to speak in front of military audiences. He does not speak in front of civilians. He's on panels with top brass and others. He’s very secretive. He gave a major address in which he called for the creation of what he called a “contractor brigade.” And I actually -- I can read you what he said. He said -- this is two years ago, before Bush called for his civilian reserve corps. Erik Prince, head of Blackwater USA: “There’s consternation in the [Pentagon] about increasing the permanent size of the Army. We want to add 30,000 people.” And they talked about costs of anywhere from $3.6 billion to $4 billion to do that. Well, by my math, that comes out to about $135,000 per soldier. And then, Prince added, “We could do it certainly cheaper.”

And so, now you have Blackwater, the Praetorian Guard for the war on terror, itching to get into Sudan. You know, something happened last year that got no attention whatsoever. In October, President Bush lifted sanctions on Christian Southern Sudan, and there have been reports now that Blackwater has been negotiating directly with the Southern Sudanese regional government to come in and start training the Christian forces of the south of Sudan. Blackwater has been itching to get into Sudan, and Erik Prince is on the board of Christian Freedom International, which is an evangelical missionary organization that has been targeting Sudan for many years. And there is a political agenda that Blackwater fits perfectly into, whether it’s Iraq and Afghanistan or Sudan.

AMY GOODMAN: And the other connections, Jeremy Scahill, between Blackwater and the Bush administration and the Republican Party?

JEREMY SCAHILL: The most recent one is that President Bush hired Blackwater's lawyer -- Blackwater’s former lawyer to be his lawyer. He replaced Harriet Miers. His name is Fred Fielding, of course, a man who goes back many decades to the Reagan administration, the Nixon administration. He is now going to be Bush's top lawyer, and he was Blackwater's lawyer.

Joseph Schmitz, who was the former Pentagon Inspector General, whose job it was to police the war contractor bonanza, then goes on to work for one of the most profitable of them, is the vice chairman of the Prince Group, Blackwater’s parent company, and the general counsel for Blackwater.

Ken Starr, who’s the former Whitewater prosecutor, the man who led the impeachment charge against President Clinton, Kenneth Starr is now Blackwater's counsel of record and has filed briefs for them at the Supreme Court, in fighting against wrongful death lawsuits filed against Blackwater for the deaths of its people and US soldiers in the war zones.

And then, perhaps the most frightening employee of Blackwater is Cofer Black. This is the man who was head of the CIA’s counterterrorism center at the time of 9/11, the man who promised President Bush that he was going to bring bin Laden's head back in a box on dry ice and talked about having his men chop bin Laden’s head off with a machete, told the Russians that he was going to bring the heads of the Mujahideen back on sticks, said there were going to be flies crawling across their eyeballs. Cofer Black is a 30-year veteran of the CIA, the man who many credit with really spearheading the extraordinary rendition program after 9/11, the man who told Congress that there was a “before 9/11” and an “after 9/11,” and that after 9/11, the gloves come off. He is now a senior executive at Blackwater and perhaps their most powerful behind-the-scenes operative.

AMY GOODMAN: And electoral politics?

JEREMY SCAHILL: Well, Erik Prince, the head of Blackwater, and other Blackwater executives are major bankrollers of the President, of Tom DeLay, of Santorum. They really were -- when those guys were running Congress, Amy, Blackwater had just a revolving door there. They were really welcomed in as heroes. Senator John Warner, the former head of the Senate Armed Services Committee, called them “our silent partner in the global war on terror.” Erik Prince’s sister, Betsy DeVos, is married to Dick Devos, who recently lost the gubernatorial race in Michigan.

But also, Amy, this is a family, the Prince family, that really was one of the primary funders. It was Amway and Dick DeVos in the 1990s, and it was Edgar Prince and his network -- Erik Prince's father -- that really created James Dobson, Focus on the Family -- they gave them the seed money to start it -- Gary Bauer, who was one of the original signers to the Project for a New American Century, a major anti-choice leader in this country, former presidential candidate, founder of the Family Research Council. He credits Edgar Prince, Erik’s father, with giving him the money to start the Family Research Council. We’re talking about people who were at the forefront of the rightwing Christian revolution in this country that really is gaining steam, despite recent electoral defeats.

And what’s really frightening is that you have a man in Erik Prince, who is a neo-crusader, a Christian supremacist, who has been given over a half a billion dollars in federal contracts, and that's not to mention his black contracts, his secret contracts, his contracts with foreign friendly governments like Jordan. This is a man who espouses Christian supremacy, and he has been given, essentially, allowed to create a private army to defend Christendom around the world against secularists and Muslims and others, and has really been brought into the fold. He refers to Blackwater as the sort of FedEx of the Pentagon. He says if you really want a package to get somewhere, do you go with the postal service or do you go with FedEx? This is how these people view themselves. And it embodies everything that President Eisenhower prophesied would happen with the rise of an unchecked military-industrial complex. You have it all in Blackwater.

AMY GOODMAN: Jeremy Scahill, thanks very much for joining us, and I look forward to seeing your book when it comes out. Jeremy Scahill's forthcoming book is Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army. Thanks for joining us.

Labels:

Amy Goodman,

books,

contractors,

Democracy Now,

Interviews,

war in Iraq

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)